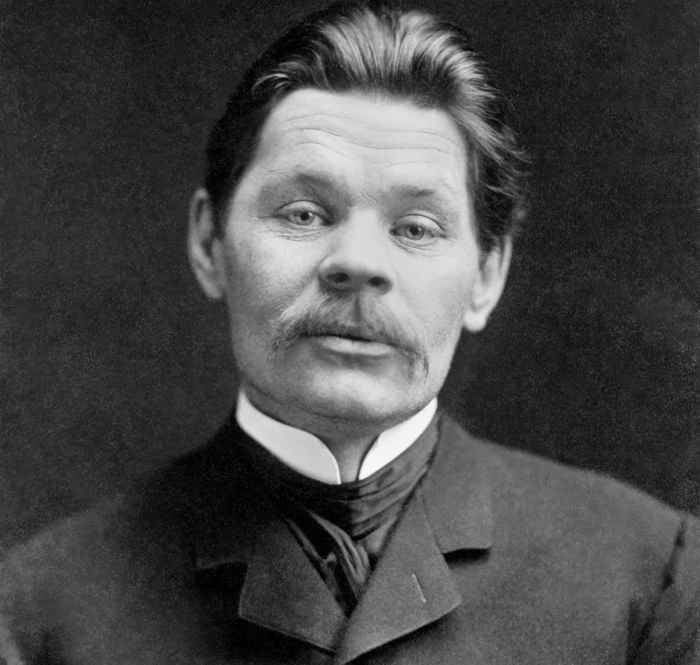

Maxim Gorky (1868-1936)

Alexei Maximovitch Pyeshkov, known as Gorky, which signifies “bitter,” was born at Nijni Novgorod in 1868. He was orphaned at nine, and was then apprenticed to a bootmaker. He ran away and wandered all over Russia, plying various trades, and reading greedily all the books he could obtain. His experiences gave him a fund of material for his remarkable stories; stories which are filled with the vigour and pathos, the gentleness and bitterness of Russian life. At the height of his career he was exiled, and did not return to his native country until after the war.

Gorky specialized in the description of the class of outcasts which he knew best. Most of his short stories deal with these people.

The present version has been reprinted from Thomas Seltzer`s Best Russian Short Stories, Boni & Liveright, New York, by permission of Jarrolds, publishers, in whose volume, Stories from Gorki, it first appeared. The translator is R. N. Bain.

One Autumn Night

Once in the autumn I happened to be in a very unpleasant and inconvenient position. In the town where I had just arrived and where I knew not a soul, I found myself without a farthing in my pocket and without a night`s lodging.

Having sold during the first few days every part of my costume without which it was still possible to go about, I passed from the town into the quarter called “Yste,” where were the steamship wharves a quarter which during the navigation season fermented with boisterous, laborious life, but now was silent and deserted, for we were in the last days of October.

Dragging my feet along the moist sand, and obstinately scrutinizing it with the desire to discover in it any sort of fragment of food, I wandered alone among the deserted buildings and warehouses, and thought how good it would be to get a full meal.

In our present state of culture hunger of the mind is more quickly satisfied than hunger of the body. You wander about the streets, you are surrounded by buildings not bad-looking from the outside and you may safely say it not so badly furnished inside, and the sight of them may excite within you stimulating ideas about architecture, hygiene, and many other wise and high-flying subjects.

You may meet warmly and neatly dressed folks all very polite, and turning away from you tactfully, not wishing offensively to notice the lamentable fact of your existence. Well well, the mind of a hungry man is always better nourished and healthier than the mind of the well-fed man; and there you have a situation from which you may draw a very ingenious conclusion in favor of the ill fed.

Read More about The Story of Devadatta 2