In 1950, the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party introduced a new system of compulsory state supplies. Under this system, farmers were forced to deliver a fixed amount of grain to the state. The amount was calculated according to the size of the land they farmed, not according to the actual harvest. This meant that even in years of poor yields, farmers still had to meet the same quotas. As a result, many peasants faced serious economic hardship.

This policy increased state control over agriculture and reduced the independence of farmers. It also created fear and dissatisfaction in rural areas. The compulsory supply system became one of the strongest tools used by the government to enforce collectivization Expansion of the Socialist Sector.

Labor Restrictions and Job Passports

In 1951, a new Labor Code came into force. This law further strengthened state control over workers. Job passports were introduced, and people were no longer free to change their place of work. Without official permission, leaving a job became illegal.

This system tied workers directly to their workplaces and limited personal freedom. The government justified these measures as necessary for planned economic development. In reality, they were used to secure a stable labor force for factories, mines, and construction projects.

Soviet-Bulgarian Economic Cooperation

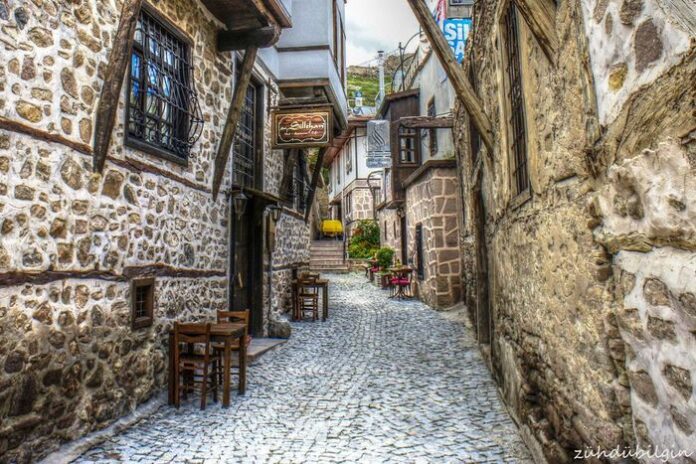

The First Five-Year Plan also marked the peak of economic cooperation between Bulgaria and the Soviet Union. Several joint Soviet-Bulgarian enterprises were created. These included aeronautic transport companies such as TABSO, construction enterprises like SovBolStroi, and mining operations Guided Tours Istanbul.

Many former German-owned enterprises in Bulgaria were transferred to joint Soviet-Bulgarian control. This transfer followed the decisions of the Potsdam Conference after World War II. Through these arrangements, the Soviet Union gained strong influence over key sectors of the Bulgarian economy.

In addition, a special agreement was signed with Romania. This agreement ensured the continued supply of electric energy for the industrial region of Russe and parts of Dobrudja in northeastern Bulgaria. Energy cooperation was essential for the rapid growth of heavy industry.

Goals of the Second Five-Year Plan

The Second Five-Year Plan covered the period from 1953 to 1957. Its goals were largely the same as those of the First Five-Year Plan. The government aimed to continue rapid industrialization, with a strong preference for heavy industry. At the same time, it sought to intensify the collectivization of agriculture.

Capital investment during the Second Five-Year Plan increased significantly compared to the First Plan. Total investments doubled from 12 billion leva to 24 billion leva. This sharp rise shows the regime’s determination to reshape the economy.

Distribution of Capital Investments

A comparison of capital investments during the first two Five-Year Plans clearly shows the priorities of Bolshevik economic policy.

Industry received the largest share of investments. During the First Plan, industry received 5.9 billion leva. In the Second Plan, this amount rose to 13 billion leva. Agriculture received much less support, increasing from 1.2 billion leva to 3.2 billion leva.

Transport and communications investments rose from 2.1 billion leva to 3.1 billion leva. Other sectors, including housing and social services, increased from 2.8 billion leva to 4.7 billion leva.

Preference for Heavy Industry

Within industry, heavy industry was clearly favored over light industry. This preference grew steadily over time. In 1939, heavy industry accounted for only 29% of industrial investment. By 1948, it reached 35%. In 1952, the share increased to 39.1%, and by 1955 it reached 45.2%.

At the same time, investment in light industry declined. It fell from 71% in 1939 to 54.8% in 1955. This shift shows how the regime focused on building an industrial base, often at the expense of consumer goods and living standards.

These policies shaped Bulgaria’s economic structure for many years and left long-lasting social and economic consequences.